Evaluations that make a difference is a collection of 8 evaluation stories from around the world which is one of the first pieces of systematic research looking at factors that contribute to high quality evaluations that are used by stakeholders to improve programs and improve people’s lives. This initiative collected stories about evaluations that made a difference, not only from the perspective of the evaluators but also from the commissioners and users. The stories in this collection tell powerful stories about the findings in the evaluations and the ways the evaluations contributed to the impact of the programs. You may access the report and all the stories here, in English, Spanish, and French.

In these weekly posts, we will be sharing each story… Comments are very welcome!!

–

Of the world’s seven billion people, only 4.5 billion have access to toilets or latrines. The remaining 2.5 billion, most of whom live in rural areas, lack proper sanitation. And nothing spreads disease faster than open defecation. Indeed, Millennium Development Goal Number 7 is to halve the population of people living without adequate sanitation. Hence the idea for World Toilet Day, which takes place on 19 November each year.

Of the world’s seven billion people, only 4.5 billion have access to toilets or latrines. The remaining 2.5 billion, most of whom live in rural areas, lack proper sanitation. And nothing spreads disease faster than open defecation. Indeed, Millennium Development Goal Number 7 is to halve the population of people living without adequate sanitation. Hence the idea for World Toilet Day, which takes place on 19 November each year.

Let us step back a few years to World Toilet Day in 2011. We’re in Murihi wa bibi, a village in the highlands of Kwale county along Kenya’s low-lying coastal strip.

Small children chase cockerels, which in a few hours will form part of the meal for the celebrations. Excitement is in the air. Why are the villagers of Murihi wa bibi celebrating? Quite simply, they are proud and exultant that there are no longer heaps of human excrement in the bushes. The community here, convinced that their age- old tradition of shitting in the bush can no longer be tolerated, has achieved a new level of freedom – freedom from disease.

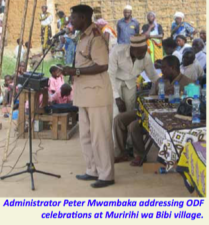

The practice had to stop; there was no way it could continue. Not with such champions as Kingi Mapenzi, Peter Mwambaka, and Josephine Mbith, who went from household to household reminding residents of the need to stop eating shit, which is what happens in communities that practice open defecation in areas used for living and farming. Kingi and Mbith are local community health workers while Mwambaka is the local government administrator. The three of them are typical of the network of local volunteers who work tirelessly to convince villagers to stop open defecation.

Not that they are the first to do this. Sanitation has long been recognised as a serious health problem in Kenya. For years, dozens of local and international organisations have attacked the scourge of open defecation from a variety of directions. The results have been varied, but more often than not, the daunting task confronting these organisations put paid to their good intentions.

Not that they are the first to do this. Sanitation has long been recognised as a serious health problem in Kenya. For years, dozens of local and international organisations have attacked the scourge of open defecation from a variety of directions. The results have been varied, but more often than not, the daunting task confronting these organisations put paid to their good intentions.

Realising that the task was simply beyond the reach of any single organization, a number of concerned individuals decided to pool their efforts – and more importantly, to position themselves as partners, not leaders, of the target communities. The idea was to lead from behind – to let the communities themselves guide the efforts to solve their common problem.

Ten of these concerned individuals decided to call themselves the Health Advocates Alliance. They registered as a legal entity with the government, but from the beginning the idea was to eschew branding and notoriety. The thinking was: If sanitation is going to work, it has to come about from the grass roots, not from outsiders. After all, villagers don’t care about the names of organisations. To emphasise the primary role of the community in this venture, the alliance adopted the term community-led total sanitation (CLTS) from a project in Bangladesh, where CLTS had proved successful in addressing open defecation.

The Alliance raises funds from a membership of 10 core individuals. These individuals are regular employees of various organisations and agencies. Although their expertise ranges from monitoring and evaluation to epidemiology, the common denominator is community health. Acting as individuals, each of the 10 members takes on remunerated consultancies from which they donate time and funding to Alliance activities. And since they work through and with community groups, the costs are minimal.

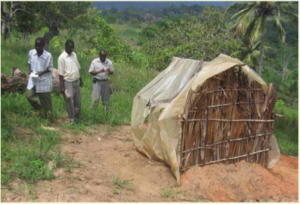

It all started in 2007. An international NGO had triggered the project at Jaribuni village in Kilifi, a neighbouring county north of Mombasa. During the triggering session, a skilled facilitator, using various participatory methodologies, led the villagers to understand the terrible consequences of open defecation. The residents of Jaribuni collectively resolved to stop open defecation by building and using latrines in a time-bound campaign led by a local committee. They gave themselves 90 days to have everyone in the village using a latrine and the local monitoring committee went around documenting the progress. The village achieved open defecation free (ODF) status just 67 days after the triggering session. To showcase this achievement, the residents and volunteers organized a simple ceremony. They invited local health officials, who were extremely impressed by the simplicity of the approach – empowering communities to analyse their own sanitation profile and to make decisions based on the realisation that they were literally eating each other’s shit due to open defecation. And the cry went up: Tumekataa kula mavi tena! (‘We refuse to eat shit any longer!’ in Swahili).

It all started in 2007. An international NGO had triggered the project at Jaribuni village in Kilifi, a neighbouring county north of Mombasa. During the triggering session, a skilled facilitator, using various participatory methodologies, led the villagers to understand the terrible consequences of open defecation. The residents of Jaribuni collectively resolved to stop open defecation by building and using latrines in a time-bound campaign led by a local committee. They gave themselves 90 days to have everyone in the village using a latrine and the local monitoring committee went around documenting the progress. The village achieved open defecation free (ODF) status just 67 days after the triggering session. To showcase this achievement, the residents and volunteers organized a simple ceremony. They invited local health officials, who were extremely impressed by the simplicity of the approach – empowering communities to analyse their own sanitation profile and to make decisions based on the realisation that they were literally eating each other’s shit due to open defecation. And the cry went up: Tumekataa kula mavi tena! (‘We refuse to eat shit any longer!’ in Swahili).

As the CLTS movement spread across Kenya, especially the coastal region, communities remained at the forefront. It doesn’t work any other way. Passionate community workers like Kingi, Mbith, and Mwambaka, who tirelessly monitored the situation every day, provided the spark that ignited the process. But they knew that to achieve total sanitation the community had to truly embrace the idea. By explaining why ODF was necessary, they provided the spark. But once the engine was running with the community in the driver’s seat, their job was confined to monitoring.

Monitoring is essential if a triggered village is to attain ODF status. This is a lesson that CLTS practitioners in Kwale and Kilifi counties learned the hard way. Initially, they thought that a triggered village would automatically translate into ODF status. With time, the importance of monitoring – and monitoring committees – gained recognition. NGO workers designed monitoring tools that the committees could use to gauge progress and identify which households required special attention.

Through this process, female-headed households and households with very old people or people living with disabilities were identified. In many places, the monitoring committees mobilised young people to contribute labour by constructing toilets for households with occupants who lacked mobility. In cases where a household could not afford construction materials, the committee approached forest authorities with the progress data to show that these few households required special support to access such construction materials as logs. That they were successful in this endeavour is nothing less than astonishing. Never before had this government body granted permission to anyone to access timber. Such is the power of placing data in the hands of aggressive community members!

Once a village attained ODF status, the residents, to show pride in their achievement, erected signposts proclaiming their achievement to the whole world and warning visitors that open defecation would not be tolerated in their turf.

Once a village attained ODF status, the residents, to show pride in their achievement, erected signposts proclaiming their achievement to the whole world and warning visitors that open defecation would not be tolerated in their turf.

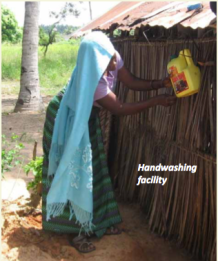

Villages even started competing with one another. To outdo each other, they kept raising the bar. They said that the monitoring indicators put together by hygiene promotion experts was not comprehensive enough to truly stop residents from eating shit. They pointed out that merely building and using a latrine was inadequate. One community fabricated aperture covers to prevent flies from breeding within in the pits. Another community, to ensure the users did not forget to wash their hands after latrine use, introduced hand washing facilities with soap or ash next to the latrine. Rival villages insisted on assigning participants in the verification missions sent out to inspect communities for ODF status. They even visited the bushes previously used for open defecation to verify the absence of faeces. In one case, where all households in a Penda Nguo, a village in Kilifi county were found to have latrines, the sanitation and hygiene promotion experts had decided amongst themselves to confer OPF status on the village. But when a member of the committee from a rival village discovered a pile of fresh faeces in the bush, the committee was left powerless to act. The Penda Kula villagers eventually decided to put a public latrine and they were eventually declared ODF when no more signs of fresh faeces were found. These are not the actions of complacent people.

Without the active participation of communities in monitoring total sanitation, the hard work and dedication of health workers would result in nothing but tired bodies and disillusionment.

Which brings us back to World Toilet Day 2011. A total of seven villages of Kwale county agreed to meet in Murihi wa bibi to celebrate their collective achievement. It was the first time that such a large number of villages would celebrate collectively. CLTS practitioners call it ‘strategic noise’. When a village – in this case seven villages – come together to formalise their refusal to eat shit, their neighbours have no option but to follow suit – to come and hear about the achievement and join in the strategic noise of celebration.

Which brings us back to World Toilet Day 2011. A total of seven villages of Kwale county agreed to meet in Murihi wa bibi to celebrate their collective achievement. It was the first time that such a large number of villages would celebrate collectively. CLTS practitioners call it ‘strategic noise’. When a village – in this case seven villages – come together to formalise their refusal to eat shit, their neighbours have no option but to follow suit – to come and hear about the achievement and join in the strategic noise of celebration.

No less than the regional director of health is invited to witness their joy of saying no to unsanitary living. The strategic noise includes testimonials from villagers. Mzee Hamadi recalls how squatting out in the bush robbed him of his dignity. The fear of stepping on snakes at night and the nightmare of finding a dry spot in the grassy patch during the rainy season was too much for him. When the movement swept his village, he was more than glad to join and stop open defecation.

His neighbour, Yusuf Ali, tells a different story. ‘At first,’ he said ‘I was not so glad. I didn’t see the importance of wasting effort and resources to build a house for shit.’ However, his wife noticed that their 2-year-old daughter Fatuma, who suffered chronic diarrhaea before Yusuf reluctantly built the family latrine, was now active and healthy. For the last 3 months, she informs the cheering gathering, Fatuma has not had diarrhaea. Even the health workers in the Mazumalume dispensary say they miss her because she no longer has to visit them. Siku hizi, twaenda hospitali kwa chanjo za kakake mdogo. (‘These days, we only visit the clinic for immunising Fatuma’s little brother.’)

His neighbour, Yusuf Ali, tells a different story. ‘At first,’ he said ‘I was not so glad. I didn’t see the importance of wasting effort and resources to build a house for shit.’ However, his wife noticed that their 2-year-old daughter Fatuma, who suffered chronic diarrhaea before Yusuf reluctantly built the family latrine, was now active and healthy. For the last 3 months, she informs the cheering gathering, Fatuma has not had diarrhaea. Even the health workers in the Mazumalume dispensary say they miss her because she no longer has to visit them. Siku hizi, twaenda hospitali kwa chanjo za kakake mdogo. (‘These days, we only visit the clinic for immunising Fatuma’s little brother.’)

The ceremony ends up with awarding of certificates to the ever-committed monitoring committee. Expressing his excitement, Kingi exclaims ‘Even my most troublesome set of villages are finally ODF!’

As a roving community health worker he knows his energy will be tested as he and his team plans to trigger Katangini, a village on the other side of the hill. But for now, he can relax and enjoy a sumptuous meal of pilau and chicken stew. Remember those cockerels?

The revelry is well deserved. And what’s more? Unlike the last 2 years when Kingi had to travel to the next county, this year’s World Toilet Day celebration is happening right here in his village. What an honour, what a great way to put the finishing touches on a successful year – and to look forward to an even better one!

The revelry is well deserved. And what’s more? Unlike the last 2 years when Kingi had to travel to the next county, this year’s World Toilet Day celebration is happening right here in his village. What an honour, what a great way to put the finishing touches on a successful year – and to look forward to an even better one!

———————-

Redempta Muendo, Kwale County Public Health Officer; Haron Njiru, Programs Director, HEADS Alliance

Kingi Mapenzi, Peter Mwambaka, and Josephine Mbith: on the ground

Story writers: Njoroge Kamau and Eric McGaw

A powerful example of how evaluations that are designed to collect data and feed results back on a regular basis, facilitate stakeholders making changes long before the final report is written (if indeed there even is a final report).

It is great to see how, as time goes on, evaluation can help users find out what effects the changes had, and further (better-informed) refinements can be made if needed.

Indeed, a very good example of how the evaluation and the programme were so closely linked that it sometimes became difficult to say where the

programme stops and the evaluation begin. Good illustration of how evaluators often work very closely with programme staff to support implementation of the findings as well!